Alexander Gray Associates presented Jack Tworkov: Mark and Grid, 1931–1982, its first exhibition of work by Jack Tworkov (b.1900, Biala, Poland—d.1982, Provincetown, MA), since recently becoming the representative of the artist’s Estate. Jack Tworkov: Mark and Grid examined the artist’s stylistic progression featuring work from different decades, and highlighted his conceptual approach to painting during the 1960s and 1970s. The accompanying exhibition catalog includes a segment of an unpublished original transcript of an interview between Tom E. Hinson, art historian and Emeritus Curator of Photography, Cleveland Museum of Art (OH), and Jack Tworkov recorded at his Provincetown studio in 1975.

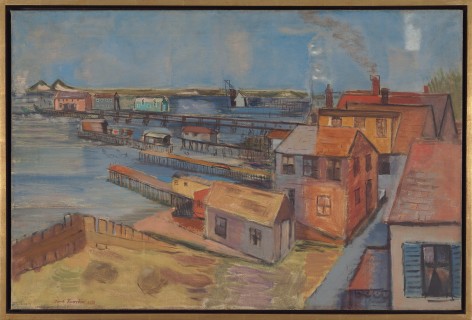

Tworkov arrived to the United States from Poland at age thirteen. He attended Columbia College as an English major, and spurred by his sister, the artist Janice Biala, he left Columbia in 1923 to begin art classes at the Art Students League and the National Academy of Design in New York. By the late 1940s, Tworkov was balancing his time between painting, his family, and teaching, working and exhibiting in New York City and the artist colony in Provincetown, MA. Although he embraced American culture, Tworkov often expressed a sense of alienation both in his public life as well as in his private existence as a deeply intellectual painter who defied the whims of the avant-garde in order to forge his own progressive and humanist approach to art. This sentiment is embodied in a 1947 journal entry where Tworkov asserted, “Style is the effect of pressure.”

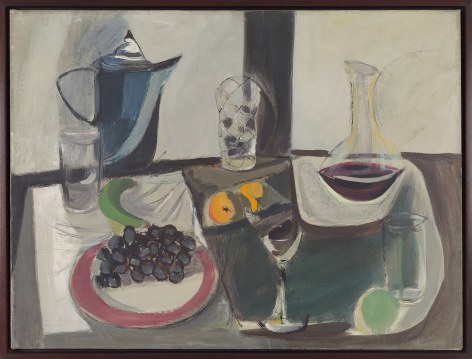

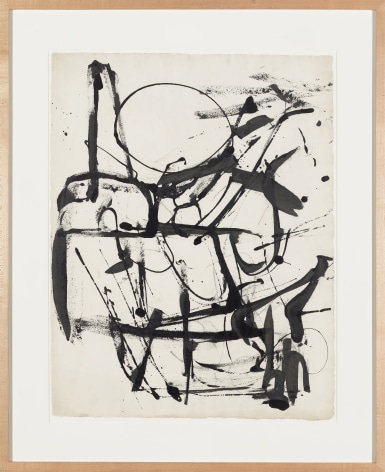

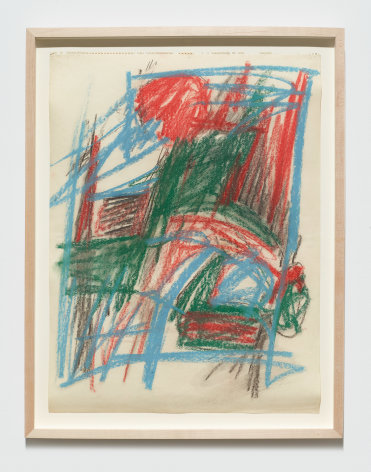

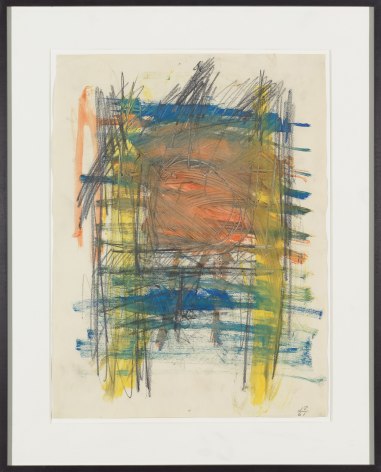

Jack Tworkov was a prominent presence in the post-war New York City arts scene. He was a founding member of the New York School’s seminal Eighth Street Club that included Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Ad Reinhardt, among others. Fairfield Porter called him “one of the more deliberate and intellectual” artists among the abstract expressionists. In addition to participating in many of the Club’s debates, Tworkov was an instrumental figure behind the 1951 exhibition 9th Street: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture at the 9th Street Gallery, New York—which included Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, and Lee Krasner. In addition to the recognition his worked received, Tworkov was a highly regarded teacher and mentor to younger generations of painters. In the summer of 1952 he taught alongside Stefan Wolpe, Charles Olson, John Cage, and Merce Cunningham at Black Mountain College where students included Robert Rauschenberg, Dorothea Rockburne, and Jonathan Williams. During this time, Tworkov developed his characteristic loose brushwork as seen in Departure (1951), a work inspired by the theme of Homer's Odyssey. The painting, an emblematic example of his work from the decade, on loan for the exhibition, offers an underlining gridded pattern delineated by sporadic swaths of color that organize the composition.

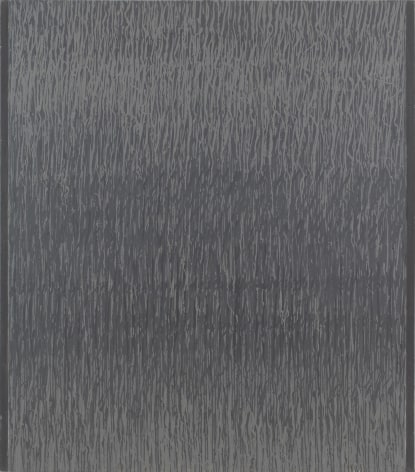

While at the forefront of the development of Abstract Expressionism, Tworkov was one of the first artists to question the movement’s commodification, cult of personality, and absorption into academia. He distinguished his views against the defined movement expressing, “…I wanted to get away from the extremely subjective focus of Abstract-Expressionist painting. I am tired of the artist’s agonies.…Personal feelings of that sort have become less important to me, maybe just a bit boring. I wanted something outside myself, something less subjective.” Richard Armstrong observed in his 1987 essay, the continual presence of a diagonal axis structuring Tworkov’s paintings that can be traced back to the early 1950s. In contrast to the action painters’ portrayal of personal struggles on canvas, Tworkov remained committed to a deliberate mark enveloped in spontaneity.

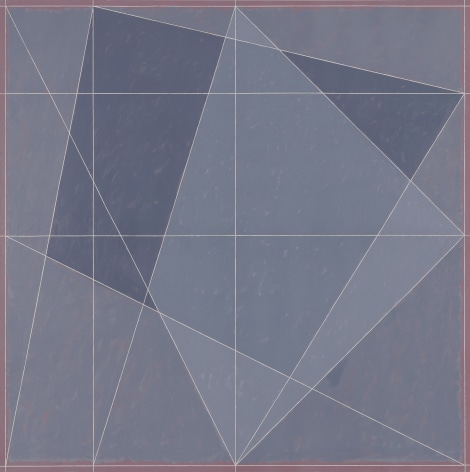

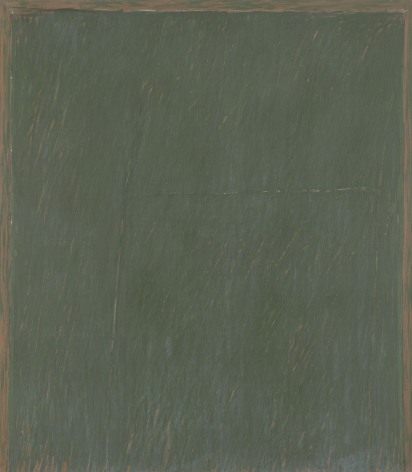

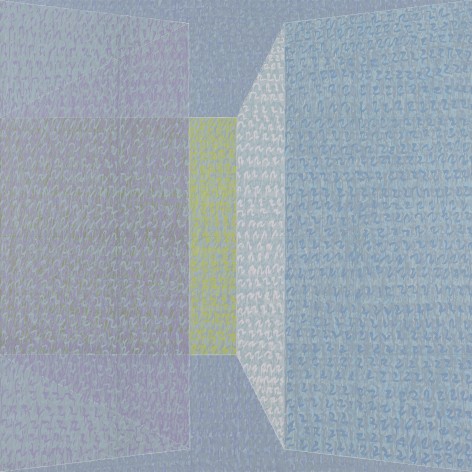

As Chair of the Art Department of the School of Art and Architecture at Yale University (1963–1969), Tworkov taught artists such as Jennifer Bartlett, Chuck Close, Nancy Graves, Brice Marden, Michael Craig-Martin, and Robert Mangold, among others. His tenure at Yale coincided with a radical stylistic shift in his painting towards diagrammatic configurations spurred by a renewed interest in geometry and mathematics. Using the rectangle as a measurement tool and foundation of his compositions, Tworkov moved away from any reliance on automatism and turned to a methodical creative process. In his words: “I soon arrived at an elementary system of measurements implicit in the geometry of the rectangle which became the basis for simple images that I had deliberately given a somewhat illusionistic cast.” By the late 1960s, Tworkov had transformed his drawings from spontaneous sketches into calculated studies and the impulsiveness of his earlier brushstrokes into measured delineations. For the artist, it was vital that the intersection of vertical, horizontal, and diagonal lines reinforced the painting’s fundamental structure, while the mark of his brush would be analogous to the undulating beat in music. Note (1968), is a signature example.

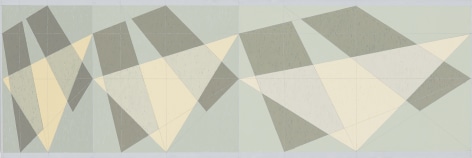

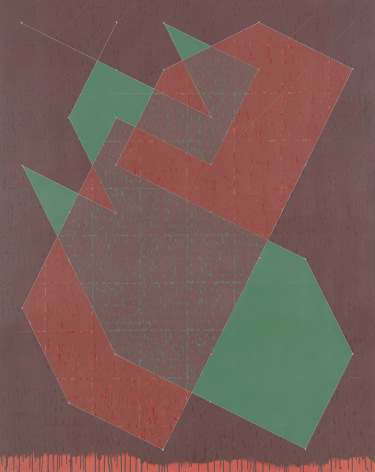

A forerunner of post-Minimalism, Tworkov entered the 1970s with a conceptual perspective towards painting that evolved into self-imposed rules and limits, yet retained the presence of the artist’s hand. Compositions from the early 1970s, larger in scale than previous work, offer playful variations on numbering systems where the divisions within the canvas followed the Fibonacci sequence of 3,5,8. Strategic linear moves underscore paintings from the “Knight Series,” one of Tworkov’s pivotal bodies of work from this decade. Knight Series #8 (Q3-77 #2) (1977), on view for the first time in New York, highlights patterns based on the various possibilities of the Knight’s move across a chessboard. Tworkov created the first painting in the series in 1975, the same year Saigon fell and the Vietnam War came to an end. He had taken an ardent position against the War, an attitude that was reflected in his paintings through metaphors of sequence that favored compositional logic and order over chaos and ambiguity.

Throughout his career, Tworkov fundamentally reinvented painting for himself by adhering to limits that defined his grids and marks and became fertile ground for his creative process, as shown in Compression and Expansion of the Square (Q3-82 #2) (1982), his final painting completed just months before his death. In his words, “The limits impose a kind of order, yet the range of unexpected possibilities is infinite.” Without forgoing the bravura that distinguished his work from the 1950s, Tworkov developed a new visual vocabulary in order to continuously investigate spatial possibilities. As the art historian Lois Fichner-Rathus wrote, “To [Tworkov] the process of personal growth as an artist is paramount in importance. Rather than producing endless variations on the solution to a single artistic problem, [he] has always felt compelled to generate new problems.”