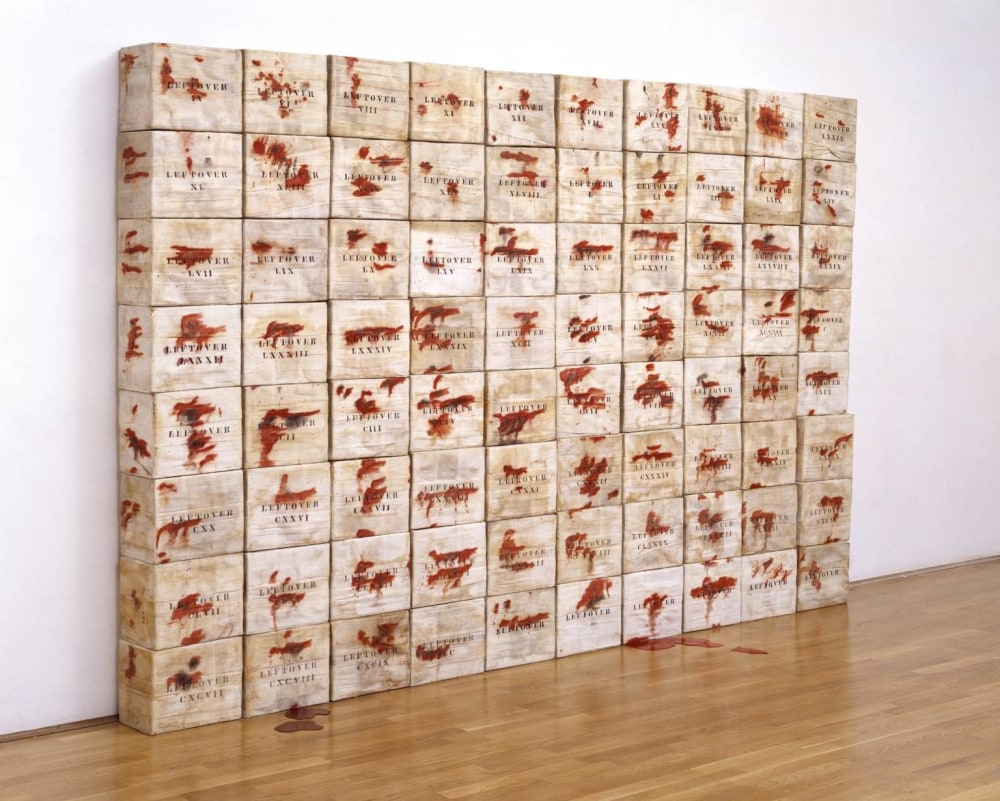

Leftovers, 1970, installation view, Tate Modern, London (2018)

Luis Camnitzer, Leftovers (1970) currently on display at Tate Modern, London, as part of the ongoing collection display Level 4: Media Networks.

Leftovers 1970 consists of eighty cardboard boxes stacked in a rectangular grid formation over two metres high and three metres wide. Sourced from a supplier in Long Island, New York, each box is tightly wrapped in surgical bandages, with glue securing the gauze, and features red ink stains that resemble blood. Stencilled on the front of each box in black ink is the word ‘LEFTOVER’ and all but six of the boxes also display a Roman numeral. Two puddles of red pigmented resin lie on the gallery floor directly in front of the boxes. The boxes are not stacked in any particular order, other than the eight by ten formation, and their position within the gallery space is not prescribed.

Born in Lübeck in 1937, Luis Camnitzer escaped with his family from Nazi Germany to Uruguay in 1939. In 1964 he moved from Montevideo to New York, where he has lived and worked since. Leftovers can be viewed as part of Camnitzer’s engagement with Latin American politics, and especially the history of dictatorship, political repression and torture in the region. After a period of unrest a state of emergency was declared in Uruguay in 1968 and lasted until 1972, during which time political dissidents were often tortured. Made in the midst of this crisis, Camnitzer’s cardboard boxes, stained with fake blood, have been interpreted ‘as containers of dismembered bodies’, which may serve to explain the significance of the work’s title (see Mari Carmen Ramírez, ‘Moral Imperatives: Politics as Art in Luis Camnitzer’, in Lehman College Art Gallery 1990, p.8). Similarly, the organisation of the boxes into a grid formation, accentuated by the numerical figures stencilled onto them, has led the critic Jan Verwoert to describe Leftovers as ‘an utterly unambiguous monument to the cruel factuality of body count logistics’ (Verwoert 2004, p.83).

Camnitzer has argued that the year 1970 represented a political turning point for his generation of artists, as it marked the beginning of the end for many revolutionary movements in Latin America. The artist has claimed, ‘Until 1970 we were using art as a political instrument. Afterwards, we found ourselves making political art’ (Luis Camnitzer, ‘Chronology’, in Daros Museum 2010, p.20).

220 boxes were originally made for Leftovers, 200 of which were used for the first exhibition of the work at the Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, in 1970 (reproduced in Daros Museum 2010, p.18). Sixty of the original 220 boxes were subsequently damaged or destroyed, with the remaining 160 being divided into two separate works, one of which is held by Tate and the other by the Yeshiva University Museum in New York. As a consequence the Roman numerals on the front of the boxes include various numbers up to 200. Initially the cardboard boxes displayed in Leftovers were stark white, but over time they have aged to become a yellow-brown colour. In an interview with Tate conservators in November 2004 Camnitzer stated, ‘In general I object to ahistorical newness’, and suggested that the current ‘blood plasma patina’ of the boxes ‘makes them stronger’.

After moving to New York Camnitzer initially made prints but in 1966 began to create text-based works such as Sentences 1966, which contains descriptions of visual situations inscribed on six chrome-plated cubes, and Leftovers 1968, which is made by pasting adhesive labels bearing the title of the work onto walls and everyday objects. Camnitzer has continued to explore the relationship between language and image, often with humour and irony, in works such as the Dictionary series (1969–70), in self-portraits consisting only of his printed name and the title and date of the work, and in his critical essays. In response to the dictatorship in Uruguay, which lasted from 1973 to 1985, Camnitzer made the Uruguayan Torture Series (1983–4) containing thirty-five prints of what seem to be harmless objects, but which are imbued with a sense of violence and repression by the title of the series. Camnitzer’s engagement with Latin American politics can be related to that of other conceptual and installation artists such as the Brazilian Cildo Meireles and the Argentine Victor Grippo, who have also addressed political subjects in their work.

Tate Modern, London

Bankside, London SE1 9TG, UK