The HIV/AIDS epidemic continues to be a lesson in power. Disease as identity is a fiction of the state, an instrument of moral authority that can decide who lives and who perishes. Make the outsider a symbol of degeneracy and then grind them down through laws which marginalize to the point of extinction. Such remains the fate of gay men and disenfranchised communities of color, both in the United States and abroad. Let’s be clear on that point: HIV/AIDS has never been the exclusive domain of gay men. However, the epidemic’s early years saw the conflation of the medical with the political, and, as Paula Treichler notes in How to Have Theory in an Epidemic, “the widespread construction of AIDS as a ‘gay disease’ … invested both AIDS and homosexuality with meaning neither had alone.”

And what is the meaning of HIV/AIDS? For Jerry Fallwell’s Moral Majority and its ilk, the epidemic was providential punishment for a life of debasement. Trade the scarlet letter for the Kaposi sarcoma. Sin on your skin, in your bones, your blood. Religion, of course, has a habit of finding virtue’s lack wherever illness arises. Syphilis was a divine punishment for promiscuity, cholera the affliction of those predisposed to intemperance and licentiousness. For the American right of the eighties and nineties, bound as it was to conservative family values and evangelical ideology, the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic were proof positive that a “gay lifestyle” brought with it depravity and death. In short, HIV/AIDS was a disease of “the Other,” a problem for “them,” not “us,” and for those in power—President Ronald Reagan the chief culprit among them—the impetus to show not just mercy, but urgency, went against the ideological worldview which had secured them power. And why should they care? As Leo Bersani noted in his essay collection, Homos, a 1993 study by the National Research Council summed it up: with AIDS cases “concentrated in zones of urban poverty, poor health care, drug addiction, and social disintegration,” prevalent amidst marginalized groups possessed of “little economic, political, and social power,” its effects upon the majority of America’s social institutions would be minimal. Their problem, not ours.

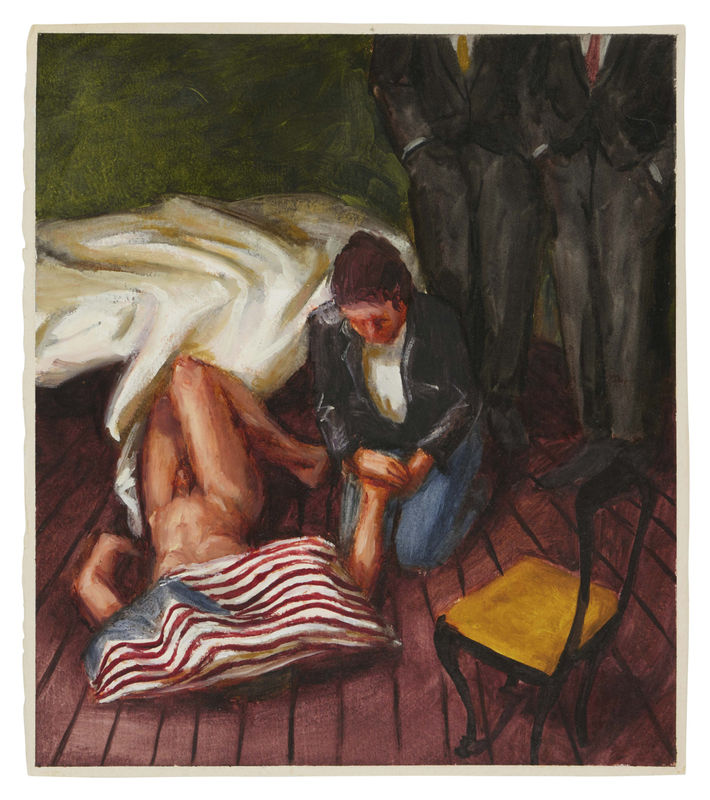

When he died at the age of thirty-two in 1995 from AIDS-related complications, Hugh Steers left behind a body of work that is at once a chronicle of the artist’s own confrontation with death’s imminence, and a surreal, at times mordant, evocation of the epidemic’s specter. In a loose style of realist painting—oils were his favored medium—Steers balanced a virtuosic play of light with an eye for color and composition that drew references from classical and modern painters alike: see glimmers of Diego Velázquez in a subject’s pose, Pierre Bonnard’s bathtub in another. Steers was particularly fond of Edward Hopper’s emptied landscapes, magical and modern as they were. Hopper understood the soft glow of loneliness like no other, and in him Steers found a kindred spirit. “It’s impossible to escape isolation,” Steers remarked in an interview from 1992, “there’s only so far you can go with another person.” One can sense the import of Hopper’s influence in the arid domestic spaces Steers would often return to as the settings for his own paintings, populated by few subjects—often just two figures were depicted, one a witness to the other’s affliction. For Steers, quotidian settings became allegories for death’s banality; unfathomably important events in someone’s life play out in the most commonplace of settings.

...

Read full article at brooklynrail.org